A question editors often ask a writer is: “Who are you writing for?” “Who is your audience?” These same questions came to mind as I opened chef Thomas Keller’s newest book, “The French Laundry, Per Se” ($75, Artisan).

During a global pandemic, climate crises, economic collapse, untold suffering, deepening civil unrest and division over questions of equality and justice, and the craziest presidential election in most peoples’ memories, why would one choose a book about two of the most expensive, exclusive, entitled restaurants in the U.S.?

Keller addresses this, to some extent, in a preface he wrote in April 2020. “Two years ago, in what now seems like another lifetime, I began working on this book. My intent at the time was to celebrate two restaurants, The French Laundry and Per Se, by telling their stories within the broader context of the evolution of fine dining.”

“I never would have imagined how dramatically its arc was destined to change,” he adds, putting into perspective a decision to go ahead with the publication of a book that could be perceived as an ode to the new gilded age in America.

Like all of Keller’s books, “The French Laundry, Per Se” is more of a work of art than a cookbook you’d open to figuring out what to fix for dinner. And like a plate that comes out of his kitchens at either of these restaurants, it’s a thing of beauty, composed of the finest elements with exquisite attention to detail.

And it tells stories. Keller recounts how after two failed restaurants in New York, he hit a low point in his life, landed in Yountville, California and found an old restaurant, called the French Laundry. Its success, along with his ideas and his food, made him famous. A decade later returned to New York to open a restaurant. People kept asking him if it would be another French Laundry, and after replying enough times, “Not the French Laundry, per se,” he realized he had the name for the New York venture.

To peruse “The French Laundry, Per Se,” it is to fall into a foodie wonderland created by a culinary imagination without borders, at least in terms of the fanciful, the elusive, the startling, the amusing, and the doubtlessly delicious. In this world, even the familiar is something different: French onion soup resembles a foamy beer in a parfait glass. Fish ‘n’ Chips is ale-battered blowfish with malt vinegar jam, and to create it the recommended equipment needed includes a chamber vacuum sealer and an infrared thermometer gun.

“This book contains more than 70 fairly elaborate recipes, which include equally elaborate components,” Keller writes. “One of the goals of this book is to give a glimpse into our kitchens, a look at the actual ingredients, recipes and processes and we use. We did not significantly alter the recipes so that they would be easier for home chefs.”

Well, there you are, kids. No Royal Ossetra Caviar with Chocolate Hazelnut Emulsion tonight.

If anything, Keller writes, the recipes have become more complex than those he introduced in “The French Laundry Cookbook,” published in 1999, and the ingredients have become increasingly refined. He and his team now work with ingredients of a quality “that would have astonished me 26 years ago,” when he opened the French Laundry.

This is part of the evolution of fine dining in the U.S., which Keller traces by breaking it into three phases. The first is dominated by the reign of restaurants like Delmonico’s, founded in 1827 in New York, and the Brown Derby, a chain founded in Los Angeles in 1926. The second saw the ascendency of French haute cuisine, inspired by the success of La Pavillion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. The wave ran through the 1960s and saw the French-born chef Rene Verdon in by the Kennedy White House.

The ‘60s, Keller writes, marks the rise of what he calls “the personality-specific styles of cooking.” It began with Paul Bocuse in France in the 1960s, and Jean-Louis Palladin, the French chef who in the 1970s, introduced “nouvelle cuisine,” a movement that freed the image of French food and introduced lighter, simpler innovative menus with a focus on exceptional ingredients.

“Jean-Louis was the first chef to go out into the country to find farmers and fishermen to get him great lamb and fresh scallops in the shell,” Keller writes. “He figured out how to get fresh foie gras in this country. He was the first chef sourcing the best eggs.”

Palladin influenced a generation of young chefs, Keller among them. “My generation wanted friendlier restaurants that also served Michelin-caliber food,” he writes. Chefs “took the fancy out of French cuisine, began creating composed plates and got rid of stuffy table-side service.”

These chefs took on celebrity status, and dining in their restaurants became a new form of entertainment.

In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve eaten a few times at the French Laundry and thought it was quite nice, although I was glad someone else was paying the bill. And I had to admit I’d be happier with a can of beans on a mountaintop or a loaf of bread and a hunk of cheese in Paris. But this is just me; for many more, a meal at Per Se or the French Laundry or any of the other cult-status establishments is a major bucket list item.

Which brings me back to the question of who Keller’s gorgeous new book is for. One answer came from, David Bredeen, chef de cuisine at the French Laundry for the past seven years and a co-author of “The French Laundry, Per Se.”

Bredeen left his Tennessee home at 14 with $21 in his pockets, after a hardscrabble upbringing, which, he cheerfully acknowledges, in no way had pointed him towards a career in the upper echelons of fine dining.

“The only thing I ever did at a country club was wash dishes,” he said in an interview. “It conjures memories of the fussy maître d’ with the rules and things.” At a Barnes &Nobles bookstore, however, he discovered books, among them “The French Laundry Cookbook.” It set him on his path.

After striving to learn culinary skills, working for free and for minimum wages, he landed a stage, a culinary apprenticeship, at the French Laundry. Even more impressively, perhaps, he got a reservation to dine there and came up with the wherewithal to pay the bill; it’s an experience he uses to underscore his belief that anyone who really wants to can dine at the world’s best restaurants.

“All the chefs who aren’t making that much money, they find a way,” he said. “We see people in the restaurant from all walks of life, from all places. And they have fun.”

The dinners may be pricey, he said (reopening after the COVID-19 shutdown, the prix fixe outdoor meal at the French Laundry is $350 and inside is $850 per person), but he emphasized that the cost supports a network of people, from the ones who do the laundry to the purveyors, gardeners, farmers and artisans as well as servers, cooks and dishwashers. “It pays for 110 employees, gardens, orchards.”

After finishing his stage at the French Laundry, he kept climbing the culinary ladder, and returned 16 years later to the Yountville restaurant as an established chef.

“It was a life-long dream,” he said. The subsequent years have been “a positive evolution and period of growth.”

The evolution? “I wouldn’t call it fine dining as much as great food,” he said. “It’s meaningful for me, the process and the cuisine. We cook food and serve our guests; but a lot of it is about philosophy — (Keller) is our philosophical guide. My job is constantly challenging, constantly evolving. There’s great energy, great team members. It’s why I never left.”

The other two co-authors, Corey Chow, chef de cuisine at Per Se, and Elwyn Boyles, pastry chef for both restaurants, share their own stories, which come down to phenomenal determination and hard work, inspired by the pathfinders such as Keller, who provided their talent with a chance to thrive.

At Per Se in New York, Corey Chow caught Keller’s eye when he was a commis — “lowest rung on the brigade” — and prepared the dish for a family meal. As top guy now, Chow writes, “It’s all about the team ... It’s about respect ... respect for ingredients, respect for technique, respect for your colleagues and the hard work that they do ... respect for teaching and mentoring. Because that is how we evolve.”

Elwyn Boyles, who was born in Wales, got his restaurant start, like Keller and Bredeen, washing dishes. Eventually, he found his place as a pastry chef. He was working in England when he saw an ad for a pastry chef at Per Se in New York and “dared to dream.”

So, to get back to the new book: Its recipe for Eggplant Parmesan may not become your go-to version for a family dinner, but it is undeniably intriguing, and it does provide a look into the world where a humble dish is recreated as an eggplant galette on a bed of charred eggplant béchamel with a garnish of tomato raisins. Even more than a glimpse into the high-energy, high-powered kitchen, is the insight into the people who chose to do this work, night after night.

What’s ahead, Keller asks. “More and better.”

The evolution of fine dining has filtered out of that realm, not only with the focus on quality ingredients but with the idea of food as a means of exploring and understanding the world, at all price points.

I recently had a cheeseburger where the server could tell me, with enthusiasm, who made the bun and who made the cheese, where the meat came from and how the onions were cooked, in balsamic. It’s not a conversation one might have had 20 or 30 years ago, but these ingredients elevated it into an extremely fine burger.

And the spotlight on chefs has illuminated how, despite the current challenges, chefs continue to do what they love, feed people.

“While few sectors have been spared the devastation, fewer still have been harder hit than the profession I know best,” Keller concludes. “One of the truths the current crisis has revealed is the value of restaurants as a social force.”

So who is “The French Laundry, Per Se” written for? Clearly, it’s a book to inspire dreams, like the 2020 version of the old Sears Roebuck “Dreambook,” a catalog for foodies as well as young chefs.

Or you might look at it this way: $75 for “The French Laundry, Per Se,” is a whole lot less than you would pay to eat at either place.

Watch now: What will happen to outdoor dining in winter?

Photos: French Laundry and Per Se

Thomas Keller

Thomas Keller

Salade Verte

Salade Verte (Green Salad)

David Breeden

David Breeden is chef de cuisine at the French Laundry in Yountville.

Soup

Cream of Broccoli Soup gets a shaving of white truffles in the fine dining world.

Peas and Carrots

Peas and Carrots, French Laundry style.

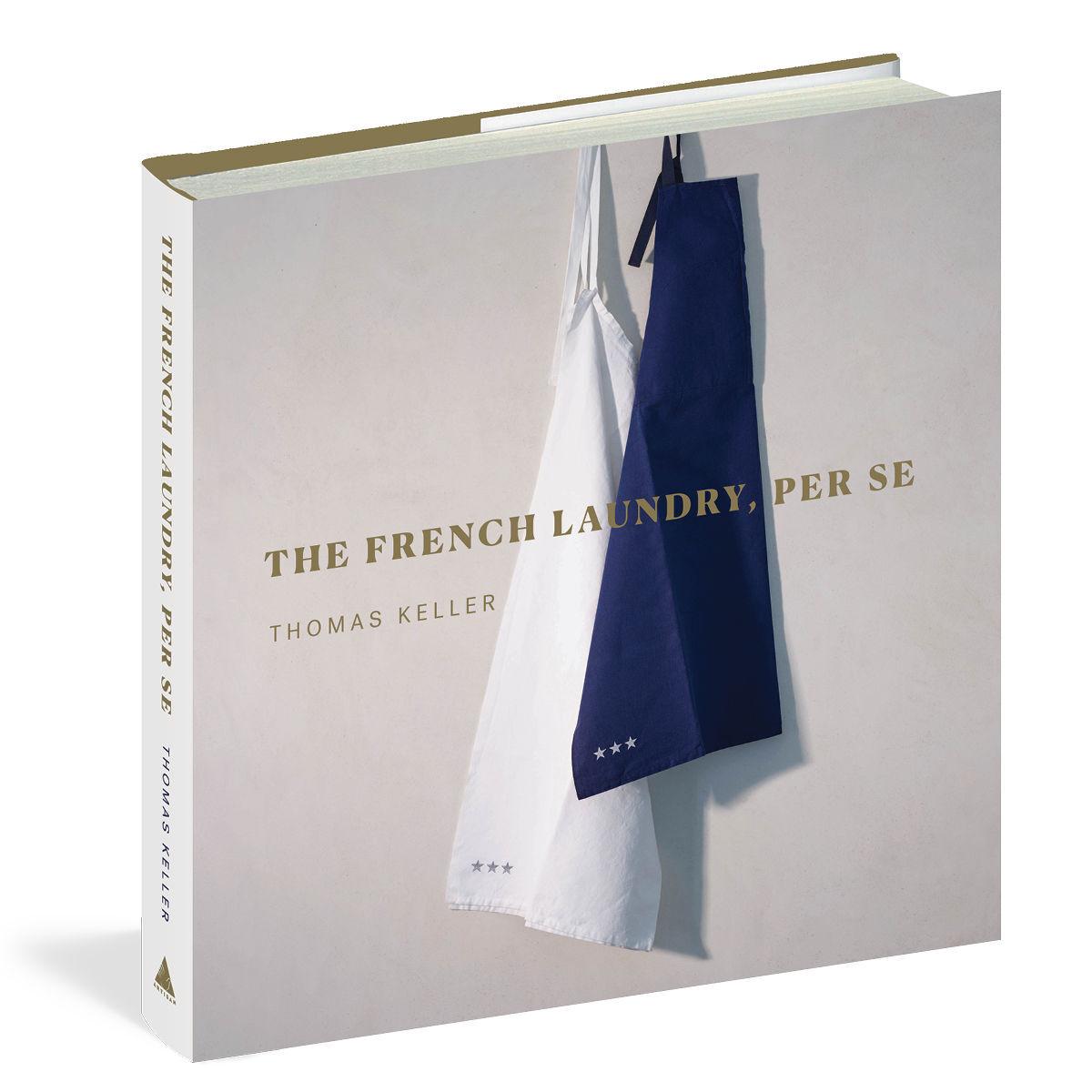

Book

"The French Laundry, Per Se," the newest book from chef Thomas Keller, is co-authored by David Breeden, Cory Chow and Elwyn Bolyes.

With our weekly newsletter packed with the latest in everything food.

October 28, 2020 at 04:47AM

https://napavalleyregister.com/lifestyles/food-and-cooking/the-french-laundry-per-se-a-philosophical-new-cookbook-from-thomas-keller-and-his-team/article_0176a6e1-23c3-5fe2-887f-0b9e206be941.html

'The French Laundry, Per Se,' a philosophical new cookbook from Thomas Keller and his team - Napa Valley Register

https://news.google.com/search?q=Laundry&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment